The drivers of human behavior are complex and context-specific. A plethora of evidence has shown that simply telling people what they should or should not do is usually not enough to make people change their actions: even when individuals are told they should do something to improve their health and why it’s important, many will not do so. This is especially the case with vaccination, where many complex factors can influence individuals’ decisions to get themselves vaccinated, including the perception that vaccination is riskier than being infected with a vaccine-preventable disease (VPD).

For this reason, PAHO/WHO recommends that countries collect data to understand the causes of low vaccine uptake and use this data to develop and implement evidence-based strategies. Additionally, using standard indictors to engage in monitoring and evaluation activities will allow for determining the impact of the interventions and adjust as needed, as well as track trends over time.

Collecting data on behaviors and social drivers of immunization can help explain why uptake gaps exist. Collecting this data can help immunization programs:

Identify and address influences on behavior;

Target and evaluate strategies in specific contexts;

Examine and understand trends over time; and

Better plan for future needs.

Videos

The WHO publication Behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake: tools and practical guidance contains step-by-step instructions and tools for collecting behavioral and social data, as well other useful information for immunization programs or organizations working to improve vaccination uptake.

Definitions:

Vaccination-specific beliefs and experiences that programs may be able to modify to boost vaccine uptake.

The proportion of a population that has received a certain dose of a vaccine in a certain timeframe.

Belief that vaccines are effective, safe, and part of a trustworthy medical system. Low vaccine confidence is distinct from, but may contribute to, vaccine hesitancy.

Motivational state of being conflicted about, or opposed to, getting vaccinated; includes intentions and willingness.

The actions of individuals and communities to seek, support, and/or advocate for vaccines and immunization services.

The spectrum of vaccine demand and hesitancy is broad and varies from total acceptance to rejection of all vaccines. There is a significant difference between vaccine refusal—when someone entirely rejects vaccination— versus vaccine hesitancy—when someone may question or have doubts about immunization. Where individuals fall on this spectrum depends on many complex factors, such as the vaccine in question, time, as well as who the vaccine is for.

It is unlikely that individuals who are extremely against vaccination will be convinced to get vaccinated, even when presented with scientific evidence that vaccines are safe and effective. Efforts should be concentrated in increasing vaccine confidence and willingness to get vaccinated among hesitant individuals.

The behavioral and social drivers (BeSD) of vaccination are defined as beliefs and experiences specific to vaccination that are potentially modifiable to increase vaccine uptake. The behavioral and social drivers of vaccination can be grouped in four domains:

- Thinking and feeling: Cognitive and emotional responses to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) and vaccines.

- Social processes: Social experiences related to vaccines, including social norms about vaccination and receiving recommendations to be vaccinated. Social norms can drive or inhibit vaccination.

- Motivation: Readiness to vaccinate, including vaccination intentions, willingness and hesitancy, but not reasons for vaccination.

- Practical issues: Experiences people have when trying to get vaccinated, including access barriers.

Follow these summarized steps from Behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake: tools and practical guidance to use the BeSD tools to assess and address the behavioral and social drivers for vaccine uptake:

Once you’ve collected and analyzed your BeSD data, you will be able to identify under which domains your uptake-related problems lie. The following table from Section 5.2 of Behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake: tools and practical guidance shows promising interventions to address problems under each domain.

Using data on behavioral and social drivers can complement other data sources from the immunization program. For example:

- Coverage data: Use to find population subgroups where BeSD data can give insight as to why these subgroups have low uptake. Qualitative data can be especially useful in zero-dose communities.

- Surveillance data: Use to understand prevalence, incidence and changes in vaccine-preventable diseases over time. High disease burden in a certain population might make it a priority for BeSD data collection.

- Census data: Use to see how uptake relates to socio-demographic characteristics.

- Social listening data: Use to see how conversations – including false information – about vaccination across various media might impact uptake.

To learn more about BeSD, read our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Behavioral Sciences and Vaccination

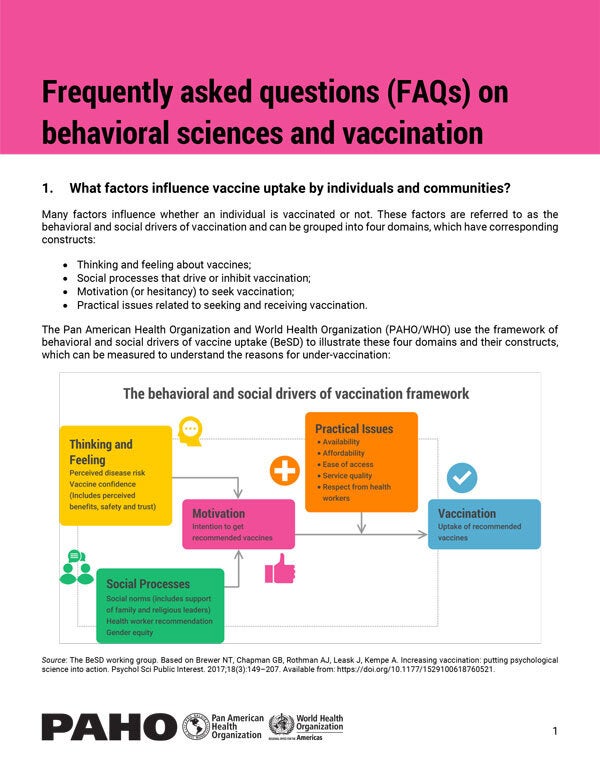

Many factors influence whether an individual is vaccinated or not; these are referred to as the behavioral and social drivers of vaccination. They can be grouped into four domains, which have corresponding constructs:

- Thinking and feeling about vaccines

- Social processes that drive or inhibit vaccination

- Motivation (or hesitancy) to seek vaccination

- Practical issues related to seeking and receiving vaccination

PAHO/WHO uses the framework of behavioral and social drivers of vaccine uptake (BeSD) to illustrate these four domains and their constructs, which can be measured to understand reasons for under-vaccination:

More information on the BeSD framework is available in Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake and the WHO position paper on this topic.

Vaccine confidence, or the belief that vaccines are effective, safe, and part of a trustworthy medical system, is part of the Thinking and Feeling domain. Low vaccine confidence is not the same as vaccine hesitancy, but may contribute to it.

Vaccine hesitancy, or the state of being conflicted about or opposed to getting vaccinated, is part of the Motivation domain. This domain includes individuals’ intentions and willingness to get vaccinated.

To be able to address a lack of confidence and hesitancy, the first step is to understand the various causes through gathering data via surveys or in-depth interviews. This data will then guide selection of corresponding interventions and later support related monitoring and evaluation.

Boosting confidence and motivations towards vaccination are important, but it is also critical to note that enhancing other drivers of uptake will also be needed, such as improving ease of access, affordability, and the quality and experience of vaccination services.

If we want to increase vaccine uptake, we need to know why individuals aren’t getting vaccinated – we cannot assume that low uptake is automatically due to low vaccine confidence or hesitancy. Immunization programs should collect data on all four of the BeSD domains to have a more complete picture of what people are thinking and feeling, their motivation, and the social processes and practical issues that drive or hinder vaccination and to then develop evidence-informed strategies that increase uptake. This process enables programs to design, target and evaluate interventions to achieve greater impact with more efficiency, and to examine and understand trends over time.

Data on behavioral and social drivers can come in two main forms: data from surveys (quantitative), or from in-depth interviews (qualitative). The best-suited tools to capture the data you need will depend on your goals and the resources available.

The joint WHO/UNICEF publication Behavioural and social drivers (BeSD) of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake provides globally field-tested and validated tools to understand drivers of routine immunization and COVID-19 vaccination. These tools are adaptable to fit your needs, but there is a core set of BeSD priority indicators (corresponding to 5 questions) that should always be included and should not be changed. The survey questions can also be integrated into other data collection activities.

Analysis of coverage data, surveillance data, census data, data from other parts of the health system, and/or social listening across a variety of platforms (social media, hotlines, community conversations, questions from the media, HW feedback, etc.) might give cues that data collection on BeSD might be required to understand what factors are influencing a population’s behaviors around vaccination.

Studies have shown that solely telling people (through communication or educational interventions) that they should get vaccinated, and how and where they should do so, will potentially increase their knowledge and confidence in vaccination, but is insufficient to change their behavior. This is because human behavior is complex, and many factors influence whether an individual will get vaccinated. Public health professionals need to consider what people are thinking and feeling, their motivation, and the social processes and practical issues that drive or hinder vaccination to develop evidence-informed strategies that increase uptake.

Form a working group that includes professionals from the immunization program, research experts, and other partners. Stakeholder involvement is also critical; make sure you involve representatives from the community where the research and interventions will be conducted. If you will be translating the survey or interview instruments, local testing of the translation with a native speaker is critical!

It is important to engage the working group and key community representatives from the start of the planning process, as well as at key milestones during data collection, analysis, and the review of findings. These stakeholders will also play a role in deciding what interventions may be most effective to address drivers or barriers identified, and how they may be adapted for the specific population or community of concern.

Share your data with interested people, groups (such as NITAGs and community groups) and organizations; present it in a way that will make sense to them. These types of individuals or organizations may also play an important role as vaccine advocates or champions and can contribute to boosting the success and sustainability of the interventions. Tell them how you conducted your research and what your main findings were.

Use your data to help you determine what types of interventions you should implement to increase vaccine uptake; more details on this are below. Additionally, you can use your data to evaluate your current interventions and make changes as needed to improve your outcomes. You can also use it to determine trends; the next time you collect data using these tools, you can make comparisons to gain a better understanding of what has changed and what has stayed the same.

Once you have collected and analyzed your data on behavioral and social drivers, you can identify which interventions might meet your needs for the different domains of the behavioral and social drivers of vaccine uptake framework mentioned above; you can see some promising interventions for each of these on page 31 of Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake.

Some examples include community-based campaigns to educate the public about vaccination (thinking and feeling domain), vaccine champions and advocates (social processes domain), and reminders for next dose (practical issues domain).

Regarding the survey tool, all countries should incorporate the 5 priority BeSD questions into routine data collection processes to support regular tracking of the measures that are most informative and highly associated with uptake. Countries with overall low coverage of childhood vaccination or COVID-19 vaccination should implement the full BeSD survey nationally every 2–3 years, or annually if there is an event that causes a rapid drop in vaccine confidence. Countries with inequities in vaccine uptake should implement the full BeSD survey and in-depth interview guides in prioritized subnational settings at least every 2–3 years.

Regarding the in-depth interview guides, coverage gaps in specific settings and the need for monitoring to improve interventions can help you determine the frequency.

Your BeSD data will provide valuable insight for monitoring and evaluating your interventions to increase vaccine uptake and allow you to see how interventions are working, where, and for whom. This can be coupled with vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) surveillance data, vaccination coverage data, and program data to paint a broader picture.

Use a monitoring and evaluation framework to identify indicators, corresponding interventions, inputs, activities/outputs, and intended outcomes. Collect data to establish a baseline before beginning your interventions. Use your evaluations to address program limitations and close gaps.

More information on indicators is available in Section 5.4 of Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake. More information on complementing BeSD data with other data sources is available in Section 5.5 of the same material.

HW are the most trusted sources of information on immunization – a recommendation from a HW can be an important nudge for an individual to get vaccinated. However, interpersonal communication is a skill that many HW are not trained in, and they don’t necessarily have all the adequate information to communicate effectively with hesitant individuals; additionally, HW are often stretched thin and may not have the time to respond to hesitant individuals’ questions and concerns in a satisfactory manner.

We also must keep in mind that HW are human beings as well and can also have varying degrees of vaccine confidence and hesitancy. Having HW who strongly support and recommend vaccination is critical to the success of immunization programs; if you have data indicating low vaccine confidence and/or vaccine hesitancy among HW, consider prioritizing interventions to address it (note: there are BeSD data collection tools for specific use with HW and the same approach and process is appropriate).

See Health worker training module: conversations with hesitant caregivers, Health worker training module: managing pain during vaccine administration and Chapters 3-9 of Communicating about Vaccine Safety: Guidelines to help health workers communicate with parents, caregivers, and patients for more information.

It is critical to engage with communities when collecting behavioral data and designing and implementing interventions to increase vaccine uptake. Community representatives should help validate your data collection tools and translations. Their insights can also help you understand their needs and perspectives in terms of vaccination. Community members should also be involved in the development of better-quality vaccination services, systems, policies, and other program strategies. Doing this will also help ensure that your interventions are culturally relevant and appropriate.

The WHO publication Human-centred design for tailoring immunization programmes: a practical guide can help you better understand community needs and perspectives.

RCCE work shares many similarities with work done within the BeSD framework. Both place value on collaboration with and listening to communities – whether it’s for intervention design, implementation, or monitoring and evaluation – and count on community input and perspectives to achieve their outcomes. Both aim to change individuals’ behavior in favor of improved health outcomes. Both need the trust of their target audience in order to be successful. In fact, applying RCCE principles – having communication that is accessible, applicable, trustworthy, pertinent, timely, and understandable by the audience – can help improve BeSD interventions.

At the same time, RCCE generally represents two main types of interventions, and to achieve high uptake, a far broader range of interventions are needed, including addressing access-related and practical issues, behaviorally informed interventions, and other types of structural and policy interventions. The BeSD framework and tools support gathering and use of data in a structured and systematic manner to help identify the appropriate tailored interventions corresponding to different types of drivers or barriers.

The framework provides a systematic, uniform way to conceptualize, measure and change factors and behaviors to increase vaccine uptake.

The BeSD data collection tools – especially the interview guides, which allow you to ask more in-depth questions – can help capture what people are saying and feeling about vaccines and vaccination, regardless of whether it’s true. This can be used in conjunction with other social listening platforms and approaches to understand what information is circulating in certain population groups and take action to address it.

To adequately understand and address the causes of low uptake, it is also vital to carry out integrated analysis with data on BeSD and other forms of data from the program (e.g., coverage and surveillance data), digital or social listening, community feedback, or other local sources. It is through the combined analysis of these various data sources that more in-depth insights may be generated.

Risk perceptions related to vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD) fall under the “Thinking and Feeling” domain of the BeSD framework. If your data indicates that your population has low confidence in vaccines being safe and effective and/or low risk perception of VPD, you can use interventions that address this, such as campaigns to inform or educate, and dialogue-based interventions involving locally trusted health workers or community representatives. You can see some promising interventions for the thinking and feeling domain on page 31 of Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake.

It is not always necessary or productive to respond to anti-vaccination activists. Before making a decision, assess the situation: Who are they? What are they saying? To whom?

An indirect response is preferred, to avoid inadvertently bringing more attention to the issue and triggering more debate. Instead, it is generally more effective to amplify accurate messaging from trusted sources on vaccine safety and effectiveness, and in doing so to corrects any false information. Work with community leaders and other partners who have the trust of your audience to reinforce your messages.

In any case, the target audience of your message should be the general public, not the anti-vaccination activist. The ultimate goal is for the general public to be more resistant to anti-vaccination stories and claims.

It is unlikely that individuals who are extremely against vaccination will be convinced to get vaccinated, even when presented with scientific evidence that vaccines are safe and effective. Efforts should be concentrated in increasing vaccine confidence and willingness to get vaccinated among those individuals who have some low confidence in vaccination and/or some degree of vaccine hesitance; addressing their concerns in an empathetic manner and answering their questions may help increase their confidence in vaccination and motivate them to seek vaccination.

Remember that vaccine hesitancy is context-specific and can depend on the vaccine in question, as well as the vaccinee.