Neisseria meningitidis (Nm), also known as meningococcus, is an encapsulated Gram-negative diplococcus that can be found intra- or extracellularly in the blood in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Due to differences in composition, there are 13 meningococcal serogroups; six serotypes (A, B, C, W, Y, and X) are usually associated with disease.

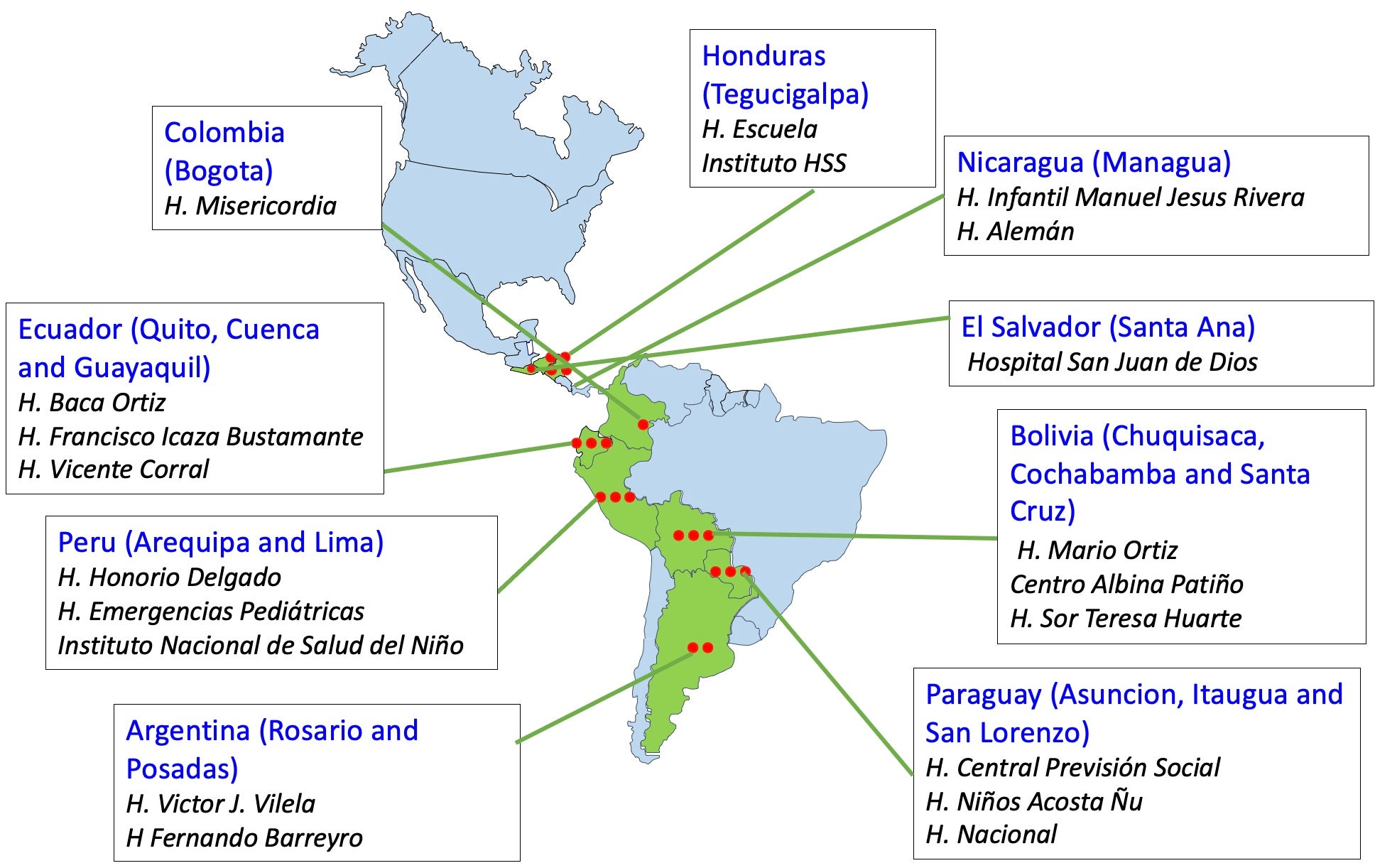

- In Latin America, the real burden of meningococcal disease is underestimated in most countries today. For example, a literature review found very different incidence rates in the period 2008-2011, ranging from less than 0.1 to 1.8 per 100,000 inhabitants, depending on the country and year. These rates represent low endemicity (<2 cases per 100,000) and are below the high-risk threshold for vaccine recommendation in national immunization programs or for outbreak control, according to WHO. However, these rates should be interpreted carefully: the challenges to reporting the disease in the Region may partially explain the differences in incidence.

- The incidence of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is highest in children under 1 year of age and remains relatively high until about age 5. Despite a declining trend in older children, it increases again in adolescents and young adults, especially when they are living together. Incidence decreases again in adults.

- IMD causes significant morbidity and mortality, with a case-fatality rate of 10-15% (and up to 40% for meningococcemia). In Latin America, it is estimated that one in five IMD patients die.

- Up to 20% of IMD survivors can have permanent sequelae; sensorineural hearing loss is the most common. Other important sequelae include speech disorders, mental retardation, motor abnormalities, seizures, visual disorders, and loss of an arm or leg in cases of meningococcemia.

Meningococcus can invade and infect different sterile spaces in the human body, but the most serious infections are meningitis and meningococcal disease. Meningitis is the most common clinical presentation.

Meningitis is an inflammation of the membranes that line the brain, cerebellum, and bone marrow, anatomical sites surrounded by subarachnoid space through which cerebrospinal fluid circulates. Meningococcemia is a rare form of infection that occurs when it spreads through the bloodstream (i.e., sepsis) with or without meningitis. What begins as an erythematous and macular rash rapidly becomes petechia and, eventually, ecchymosis.

Meningitis and meningococcemia can rapidly lead to stupor, coma, and death.

Meningococcus is transmitted by direct contact (person to person) or by contact with nasopharyngeal secretions (droplets) of an infected person. This usually occurs during close contact such as coughing, sneezing, kissing, or long-term contact such as living in close proximity to others.

Meningococcus can colonize the human oropharynx, dangerously causing carrier status. It can be passed on to someone else as it progresses to an invasive disease resulting in meningitis, septicemia/meningococcemia, or both. The highest prevalence of carriers with meningococcus in the nasopharynx is among adolescents and young adults; it is less common in young children and adults.

Susceptibility to meningococcal infection is universal: everyone is susceptible to infections caused by this bacterium. However, some conditions increase susceptibility: overcrowding, active or passive exposure to tobacco smoke, and concurrent upper respiratory infections. People with certain chronic diseases are at increased risk of invasive meningococcal infection.

-

Distribution and seasonality

The distribution of invasive meningococcal disease is highly specific; there are regional variations in serogroups, peak season, and incidence. Regarding seasonality, in Europe and the United States the highest incidence of cases is observed during the winter and spring. In sub-Saharan Africa, cases usually increase during the dry season.

-

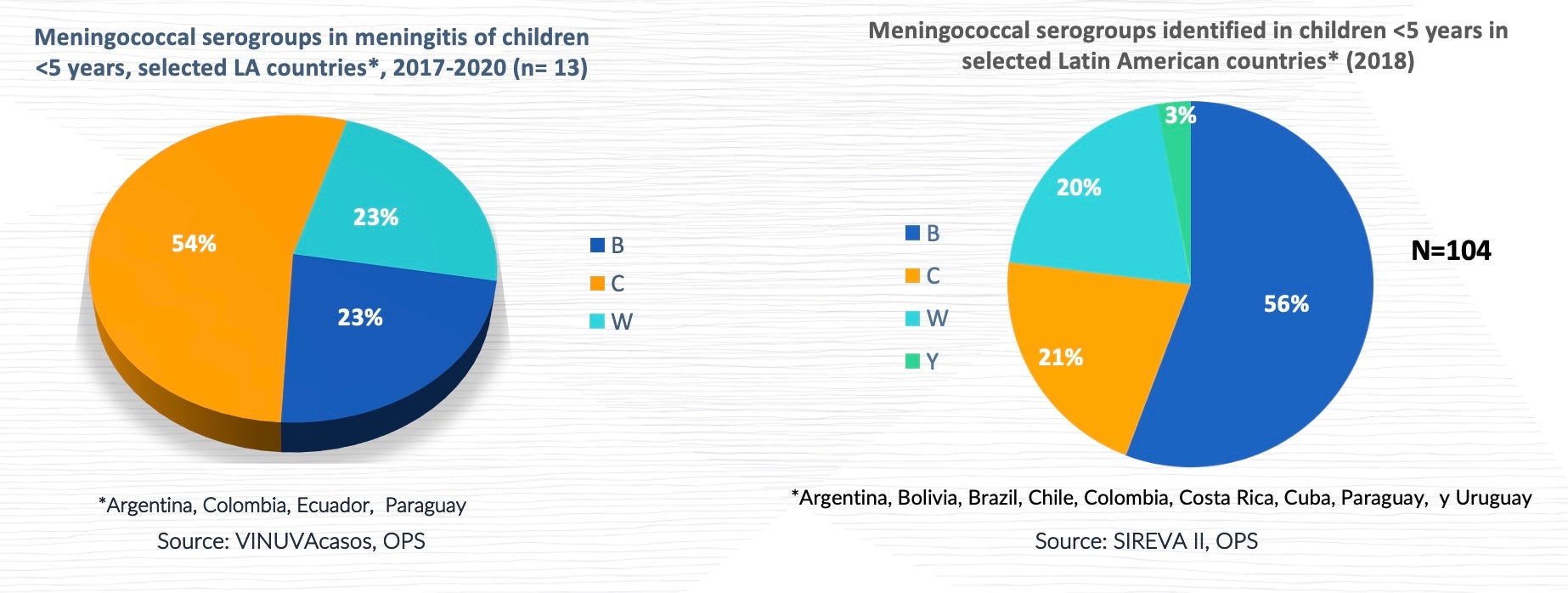

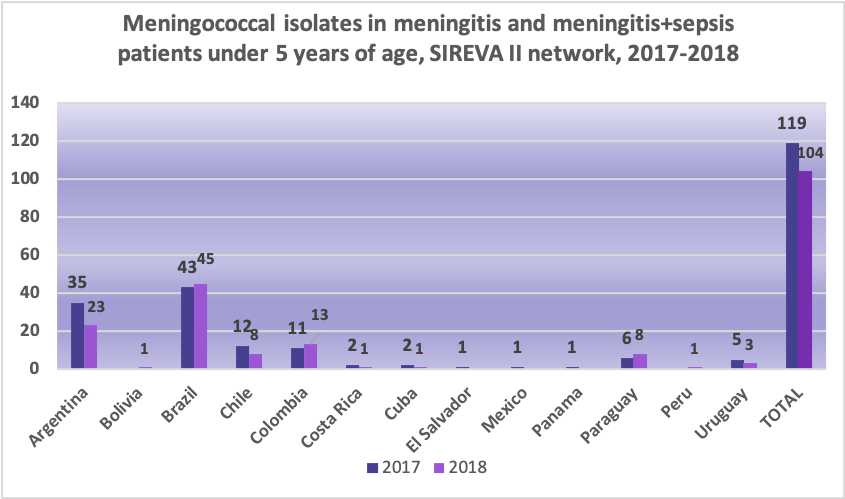

Prevalence of meningococcal serogroups

Globally, serogroup A used to be the most common causal agent of invasive disease in infants under 1 year old, and the geographical area most affected by this serogroup was sub-Saharan Africa (African belt). Serogroup A has circulated in the Region of the Americas (North America and Latin America) and the Caribbean for the last 65 years. However, serogroup A has decreased in the African belt due to the introduction of the vaccine. Most cases of serogroups B and C occur in Europe and the Americas, while serogroups A and C are the most common cause of IMD in Asia. Since the mid-1990s, there have been increases in IMD caused by serogroup Y in the United States and Israel, while serogroup X has caused local epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, a growing proportion of cases of serogroup W infection has been identified.

Immunity can be acquired passively via the placenta or actively through prior infection or immunization. The immune response to clinical and subclinical infections is of unknown duration. There is a different immune response to each of the three types of available vaccines: polysaccharides, conjugates, and recombinants.

Polysaccharide vaccines have limitations: they do not induce an immune response in children under 2 years of age, have little effect on carriers, result in a decreased level of protection within a few years, and do not generate a memory response. Conjugate vaccines produce a good and long-lasting antibody seroconversion response, including in children under age 2, by inducing immunological memory. In addition to inducing immunological memory and secondary humoral responses, they have been shown to produce herd immunity by reducing bacterial colonization of the respiratory tract in vaccinated people, thus reducing transmission to third parties, including adults. Recombinant meningococcal B vaccines produce long-term individual protection. To date, there has been no demonstrated effect on carriers.

.