In Peru, as well as in various countries in the Americas region and the world, gender violence is not only a social problem but a serious concern for public health that deeply affects women, adolescents, and girls. This is how the problem transcends ages, nationalities, and borders.

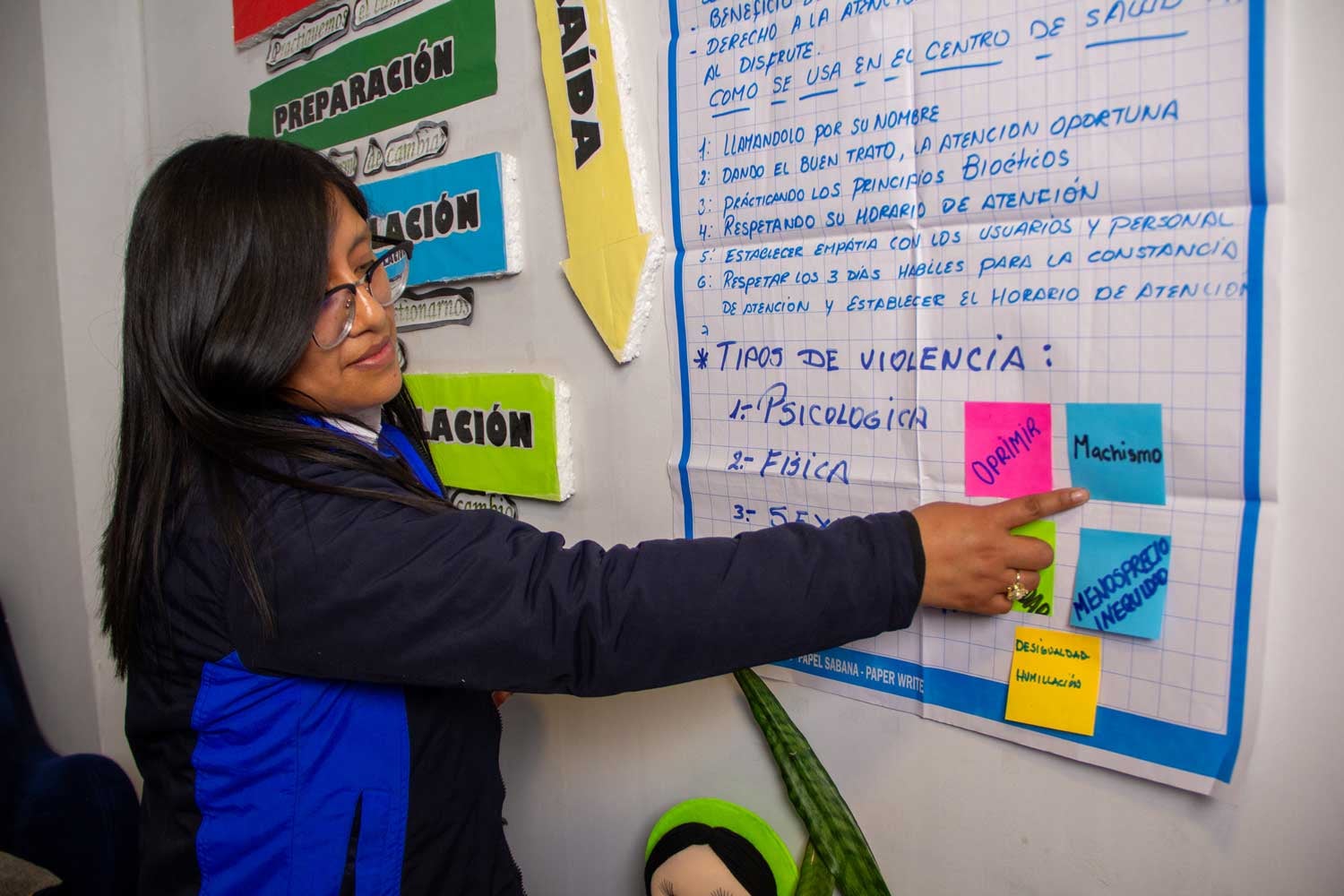

According to the Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES) of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, in 2023, "53.8% of women reported having been victims of psychological, physical or sexual violence, at some point by their husband or partner; a lower percentage than that obtained during 2022 (55.7%)". Regarding this, among the most common types of violence according to those surveyed, psychological and/or verbal violence (49.3%), physical violence (27.2%), and sexual violence (6.5%) stood out.

This situation is even more worrying for vulnerable populations, such as migrants and refugees, as they face additional barriers: lack of documents, support networks, and knowledge or facilities for accessing health services. Faced with this reality, the country has strengthened its response system through regulations and staff training that allow the implementation of a comprehensive care route without distinctions.

A route designed from the first level of care

The Community Mental Health Centers (CSMC) are at the heart of this strategy. Designed to respond to each patient's needs, they provide care free of charge.

The CSMC prioritizes a humanized approach, avoiding re-victimization and offering a safe space where victims can rebuild their lives. Trained health professionals identify signs of violence from the first contact, either through referrals or by direct demand from patients.

Similarly, the Health Centers at the first level of care are also instances where these cases are usually identified. Maria Isabel Escobar, an obstetrician at the Cooperativa Universal Health Center in East Lima, in charge of the sexual and reproductive health component, explains: "In the first prenatal check-up, we identify many patients who have been victims of violence, and they don't know how to react when we ask the screening questions. They cry or remain silent. Then, we guide them through the process that includes mental health care with the establishment's psychologist."

The diversity of those seeking help

The current route allows for any woman or member of the family group to be treated without distinction, whether they are Peruvian or not. Santa Anita is a district of Metropolitan Lima with a large migrant population. There, psychologist Monica Molina describes the challenges they face: "Migrant women often arrive with a great emotional burden due to the violence suffered in their countries of origin and the difficulties of settling here. They often lack social support, but here we try to provide them with a safe space where they can begin to rebuild their lives."

In other regions of the country, the situation is similar. Jaqueline Palomino, regional coordinator of Mental Health in Junín, says: "The fear of being deported and legal difficulties are huge barriers, but we work to guarantee them warm, immediate, and timely care." In this region, they have 16 community mental health centers and 13 specific modules for violence care, which are essential structural instances to also care for migrant women, who face greater risks due to the lack of economic stability and documentation.

Now, the care route can also begin or continue in a health establishment with a higher level of resolution. Regarding this problem, the Hipólito Unanue National Hospital in East Lima cares for between 120 and 130 foreigners annually, mainly women from Venezuela and Colombia.

At Hipólito Unanue, the arrival of a victim of violence activates a protocol designed to immediately and comprehensively care for whoever needs it. Patricia Romero, obstetrician, explains the procedure: "The first thing is to identify the case and refer it to the gynecology-obstetrics area. There, the multidisciplinary team activates the Violet Code and coordinates with the Prosecutor's Office, the Police, and other institutions to guarantee comprehensive care for the patient."

Romero also highlights that care does not discriminate: "Care is multidisciplinary, free, and a priority. It does not matter if the patient does not have documents or is from another country. We welcome them all because providing the most immediate care possible is important." However, the challenge is immense: "Many patients arrive without verbalizing that they have been victims. Some are admitted for other conditions, such as poisoning or injuries, and only after several questions do they reveal that they have suffered violence," he concludes.

Stories that transform lives

Throughout Peru, health teams work to transform violence stories into resilience. Beyond the numbers, each case attended represents a life that regains hope and a society that advances towards a life free of violence. As William Aguilar, head of the Mental Health Department at the Hipólito Unanue hospital, highlights: "The work is not only technical but also emotional and human. We care for each patient with the commitment that their story can change."

The testimonies of patients who have received care are a reminder of the human impact of this system. Víctor Tarazona, a psychologist at the Santa Anita CSMC, recalls the story of Carmen, a Venezuelan woman who was treated at his facility and who, thanks to the psychological support she received, was able to break away from an abusive relationship and build a new life for herself and her daughter. "She told us that she found a place of rest here from her worries… Now she has the courage to move forward independently, without depending on her aggressor," he says.

This care route also serves Peruvian women who are not immune to suffering violence. In Junín, Lisbeth, a young pregnant woman, found the necessary support to overcome domestic violence. "I learned that I do not have to tolerate violence. Now I know what I deserve and how to protect my baby," she shares excitedly after receiving psychological counseling.

Obstetrician Isabel at the C.S. Cooperativa Universal comments on another case: "I remember that during a prenatal check-up, a patient tested positive for violence, but her husband came into the office violently, demanding to know what I was asking his wife. The woman was crying, but I supported her and continued with the questions. In the end, he admitted that he hit her and asked for help. We referred them to psychology, and then, when I met them sometime later, the husband thanked me. For me, that was a reminder that acting promptly can change lives, not only for the victims but also for the aggressors willing to transform themselves."

A challenge and a network of hope

Gender violence is not only a personal tragedy but a public health problem with profound consequences for the victims and society. As Cristian Matamoros, regional director of Health of Junín, explains: "Violence affects everything from the family to the social sphere and has repercussions on the appearance of emotional disorders, such as depression or anxiety, which can even lead to suicide attempts."

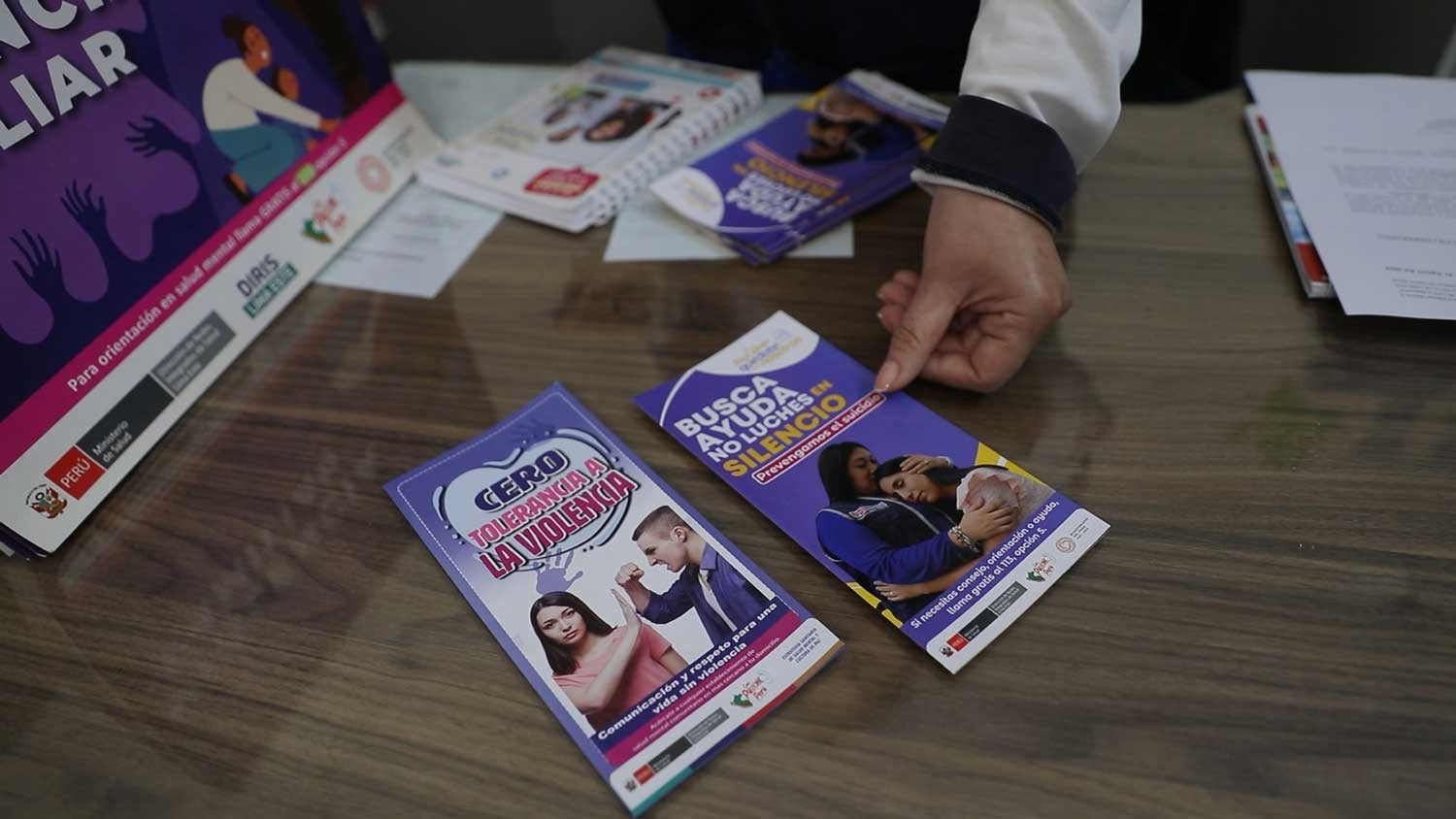

Constant and emotionally demanding work requires adequate training. The training provided by PAHO, in coordination with and in support of the Ministry of Health, has played a crucial role in strengthening the skills of health teams nationwide and has allowed health professionals to develop evidence-based interventions, improving the quality of their care. Sandy Aldana, a therapist at the Mental Health Center in Chilca (Junín), shares: "These training sessions improve our technical skills but also help us strengthen our sensitivity and empathy. They remind us that we are here to change lives."

With PAHO's technical cooperation, the Ministry of Health has not only prioritized staff training but also developed regulatory documents that unify the standard of care throughout the national territory. In this way, Peru aims to address violence with a focus on gender, interculturality, and intersectionality, adapting to each community's cultural context.

In this path to end violence, PAHO/WHO will continue to support the country in strengthening the institutional response of health services to address the problem and reinforce the care pathway. Likewise, mechanisms will be established to prevent violence during the stage of falling in love, actions to promote and ensure mental health care for pregnant women, taking as a reference the framework of strategies for the prevention of violence against women RESPECT, and the INSPIRE strategies.