For more than 30 years, ANLIS–Malbrán, the Antimicrobial Service of Argentina's National Institute of Infectious Diseases, has been working daily to tackle antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a silent threat to global public health

June 2022

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the greatest threats to global health. AMR means that microorganisms (bacteria, parasites, viruses, and fungi) are increasingly resistant to the drugs used for their treatment, known as antimicrobials. Although AMR occurs naturally through genetic changes, it is amplified by improper use of these drugs.

Antimicrobial resistance has effects on people's daily lives that are often not easily noticed. Microorganisms begin not to respond to medications, infections become more difficult to treat, the severity of symptoms increases, health systems need to provide more care, and people face a greater risk of death.

The development of antimicrobial resistance is not a phenomenon that concerns only human health. Areas such as livestock, agricultural production, and the environment are also involved, making AMR containment a challenge that must include these sectors.

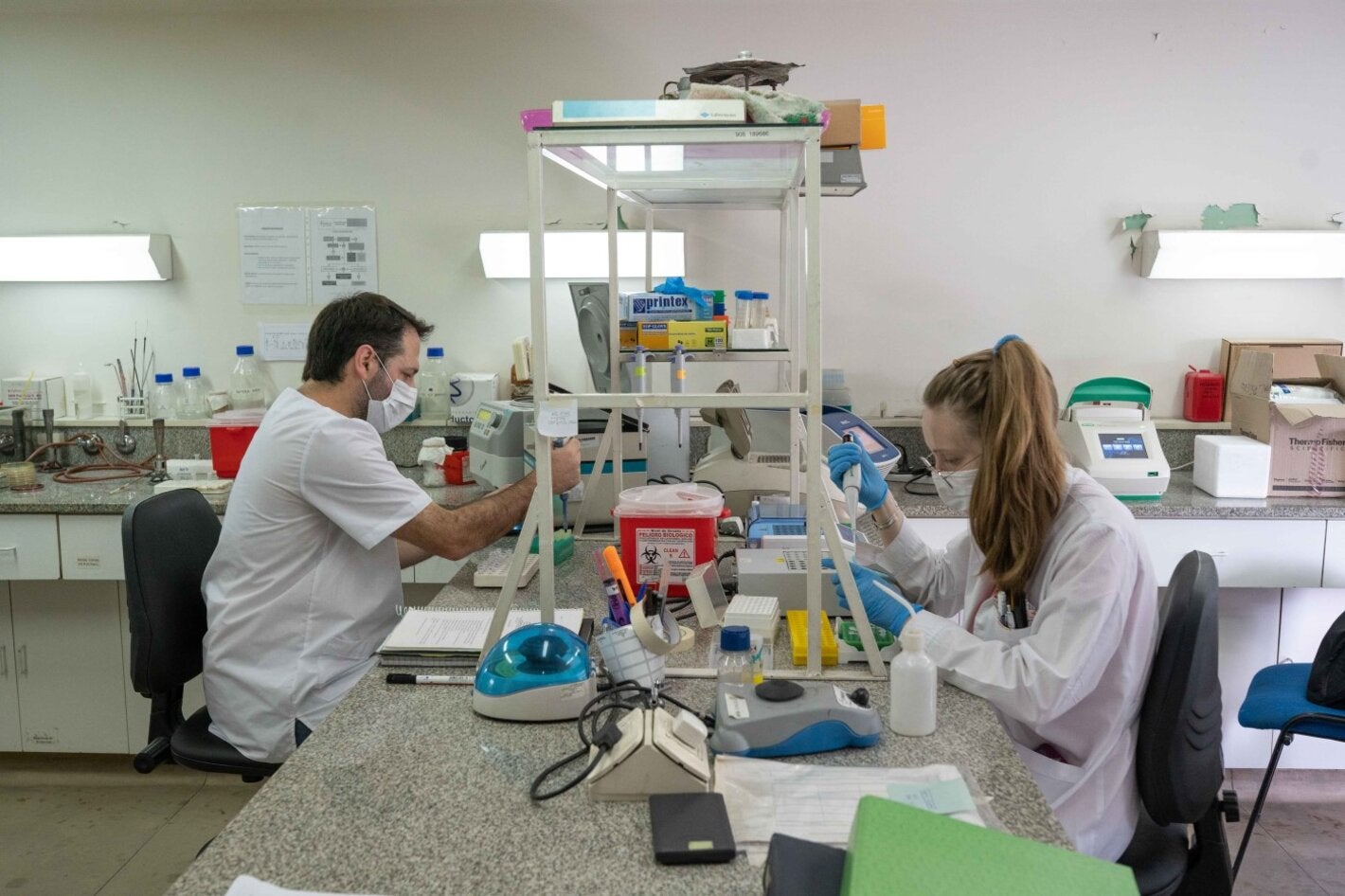

Malbrán Institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where the Antimicrobial Service is located. PH: World Health Organization

Various laboratories and institutions throughout the world are dedicated to this goal. For more than 30 years the Malbrán Institute’s Antimicrobial Service has been working in this area with a multidimensional approach that addresses five strategic areas: referential diagnosis, surveillance, applied research, external quality assessment, and training of human resources.

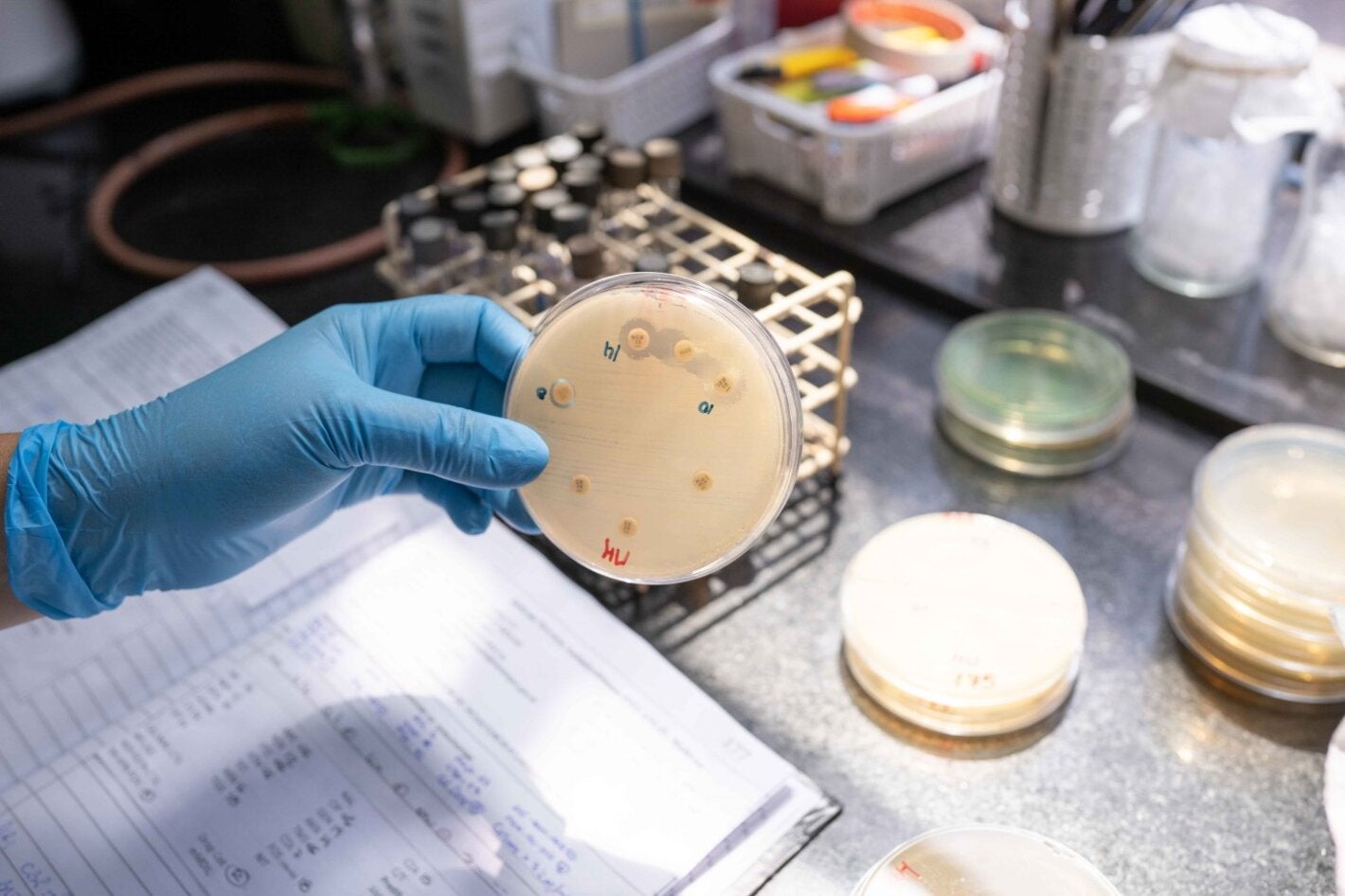

Identification and detection of resistance mechanisms in the samples received by the laboratory. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization

Recording the results of microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization

As part of its work in referential diagnosis, the service receives daily samples of resistant bacteria from microbiology laboratories throughout Argentina and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. These samples are identified and analyzed by a specialized team in order to evaluate resistance mechanisms and, if necessary, offer treatment options to health centers.

The Antimicrobial Service coordinates the National Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (WHONET–Argentina). which gathers information on AMR in communities and hospitals from 94 laboratories throughout the country. These data are analyzed and used to generate key AMR statistics at the national, regional (ReLAVRA+ ) and global (WHO-GLASS) levels in order to understand, contain, and make decisions on resistant pathogens in hospitals and communities.

Testing for biochemical identification of microorganisms and referential diagnosis. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization

"We approach our work as a constant scientific challenge; but we know that there is always a person behind each sample we receive," says Celeste Lucero, a microbiologist at the institute. "We offer answers to health teams, options for each person to have better treatment".

Manual detection of resistance mechanisms. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

Reference strains stored for decades in a freezer at -70°C. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

The service’s quality standards are among the highest in the world. It offers quality assessment programs and helps laboratories in Argentina and the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean implement methodologies and technologies.

The service coordinates three external quality assessment programs: the National Quality Control Program on Bacteriology, for 445 clinical laboratories in Argentina; the Latin American Program for Quality Control in Bacteriology and Antimicrobial Resistance, for 17 national reference laboratories in Latin America; and the Caribbean External Quality Assessment Program on Bacteriology and Antimicrobial Resistance, for 12 national reference laboratories in the Caribbean.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

Under the One Health approach, the service also transfers AMR-related technologies and methodologies to institutions in the fields of animal health, food safety, and the environment. This collaborative, multidisciplinary, and multisectoral approach makes it possible to address health threats by recognizing the links between human and animal health, and the environment in which they coexist.

Bacterial culture tested on different antibiotics. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

The Antimicrobial Service has been collaborating with PAHO as a Regional Reference Laboratory on AMR since 2000, and as a PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center since 2020. Based on the information provided by the service, in 2010 PAHO issued the first regional epidemiological alert on resistance mechanisms with the potential to render ineffective a large number of broad-spectrum antibiotics used to treat different infections. The service is currently involved with both organizations in different projects to address the problem of antimicrobial resistance.

Supplies used to prepare culture media, stored in a cold room. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

"We are passionate about our work. It is a source of immense pride to be part of this service, which is a national and regional reference entity and PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center. It is the most that a microbiology professional who studies antimicrobial resistance can aspire to," says Paula Gagetti, biochemist.

Analysis of a phylogenetic tree generated from genomic sequencing data in the service's genetics laboratory. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

The work team, composed of renowned professionals from the fields of microbiology, biotechnology, chemistry, and biology, has a long history in the service, and its members are passionate about their work. They transfer their knowledge to other laboratories through training on antimicrobials and the use of analysis systems.

Extracting DNA from bacterial cultures. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

"When we find a new mechanism of antimicrobial resistance, it's a revolution and we know that tough weeks of work await us. But we have been a team for years, and that allows us to work well. If we have to put in more hours, we do that. It's a challenge and a great responsibility," says Diego Faccone, a biotechnologist at the Antimicrobial Service.

Performing molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), for genotypic characterization of samples sent by hospital laboratories in Argentina for detection/confirmation of specific resistance mechanisms. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

Analyzing the results of genomic sequencing of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

The institute's work allows Argentina, as well as Latin America and the Caribbean, to develop new health technologies, alert the region when potentially dangerous resistance mechanisms arise, and strengthen other laboratories to ensure their quality. Its more than 30 years of daily dedication to service has made it a key player in tackling AMR in Argentina and throughout the world.

Biochemists Celeste Lucero and Paula Gagetti, and biotechnologist Diego Faccone at the Malbrán Institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina. They have been working together for more than 20 years and are part of the Antimicrobial Service that has studied thousands of bacterial isolates. PH: Sarah Pabst/World Health Organization.

"The Malbrán Institute's Antimicrobial Service has been key in responding to antimicrobial resistance in Latin America and the Caribbean. From surveys aimed at continuous quality improvement to the dissemination of knowledge and experience, the Malbrán Institute (PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center on Antimicrobial Resistance) has contributed significantly to making this a region of the world with one of the most reliable and recognized AMR monitoring and surveillance systems," said Dr. Pilar Ramón-Pardo, coordinator of the PAHO/WHO Special Program on Antimicrobial Resistance.