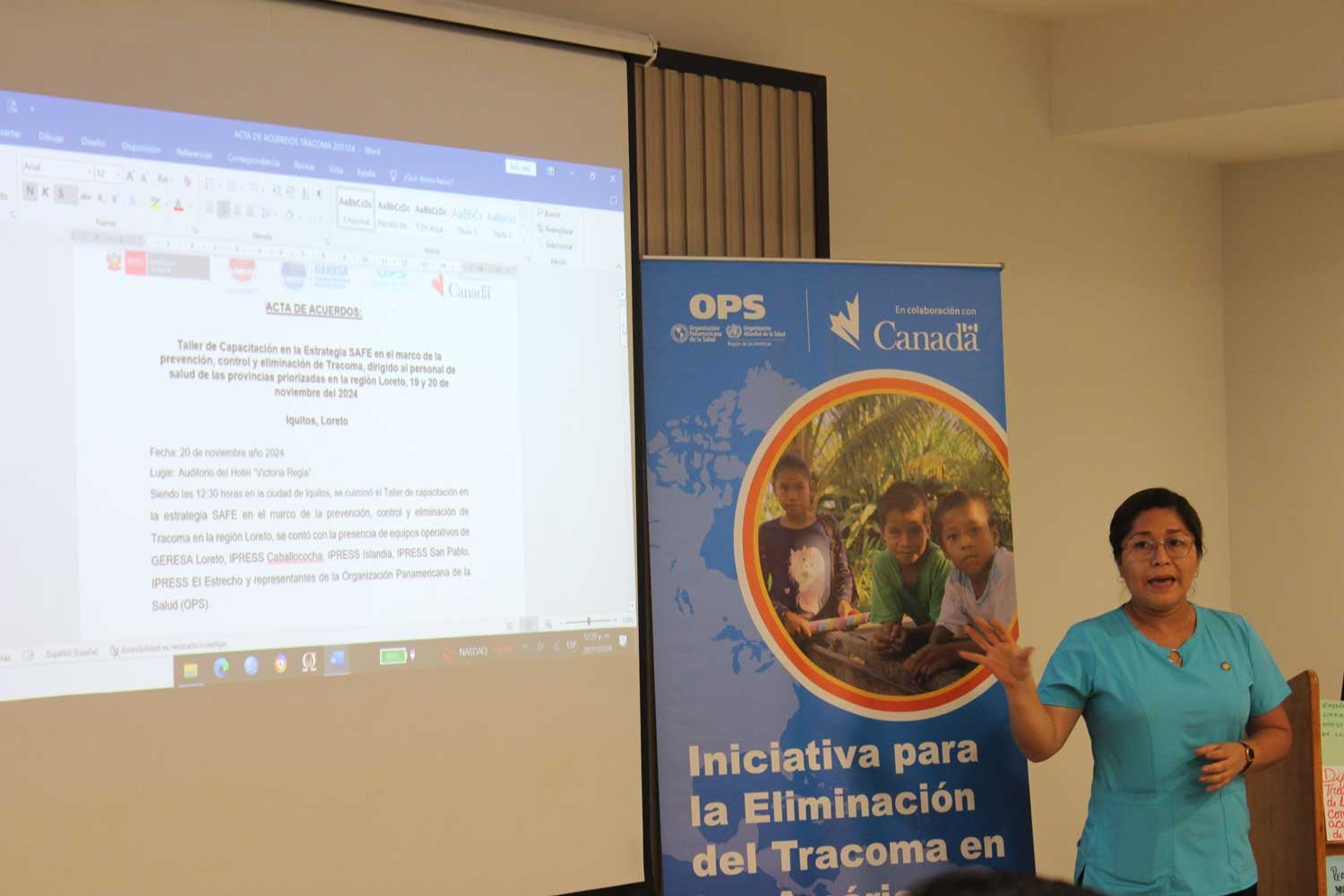

Iquitos, Peru, 22 November 2024 (PAHO/WHO).– "We have remote communities, but it is not impossible to reach them. We’re going to see how we get there and change the way people think about hygiene practices, not only for hands but also for faces," said Rosa Cárdenas, manager of the Islandia Health Center, after participating in a SAFE strategy workshop for the prevention, control, and elimination of trachoma. The workshop was held on 19-20 November in the city of Iquitos in the Loreto region of Peru. The activity was organized by the regional health authority of Loreto (GERESA) and the Ministry of Health (Minsa), with technical cooperation from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide, but it is also a neglected infectious disease (NID). NIDs mainly affect communities in vulnerable situations due to their living conditions, usually lacking access to safe water or adequate sanitation, and having other characteristics that accentuate health inequities. However, trachoma can be eliminated as a public health problem. To achieve this, the World Health Organization (WHO) promotes the SAFE strategy, which integrates surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and improvement of environmental conditions.

With support from the Government of Canada, PAHO is implementing a project in 10 priority countries to improve the health of communities, women, and children by eliminating trachoma in the Americas. In Peru, together with Minsa and GERESA Loreto, comprehensive interventions will be implemented for prevention and clinical care, and the social and environmental determinants of health will be addressed in areas where people are at risk of contracting this disease, and where conditions may worsen if the population already suffers from it.

The training included both theory and practice aimed at strengthening the competencies of health personnel from two of the provinces selected for project implementation: Putumayo and Mariscal Ramón Castilla. Fourteen health professionals arrived the previous day by river and air to update their skills in identifying risk factors, their knowledge of prevention and health promotion measures related to personal and environmental hygiene, and how to monitor residual chlorine in drinking water.

It was also important to plan for replication of the training in the participants’ own health areas, starting with a situation analysis in each community, using tools such as problem trees to plan effective interventions in each context. A demonstration and practical session on community hand washing and facial hygiene highlighted the ways people can be taught essential hygiene practices to prevent trachoma and other diseases that have the same causes.

Finally, participants discussed the importance of health personnel as key actors in communicating messages and helping to change behaviors. Educational posters on trachoma prevention and eye health––updated and validated in local communities––were handed out along with audio materials in Spanish and native languages such as Ticuna and Murui. These resources provide timely information to the population and promote healthy practices in the areas with the highest prevalence of trachoma.

This activity strengthened Peru's commitment to the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem. The training in Iquitos was a critical step in ensuring that at-risk populations have access to sustainable interventions that improve their quality of life.