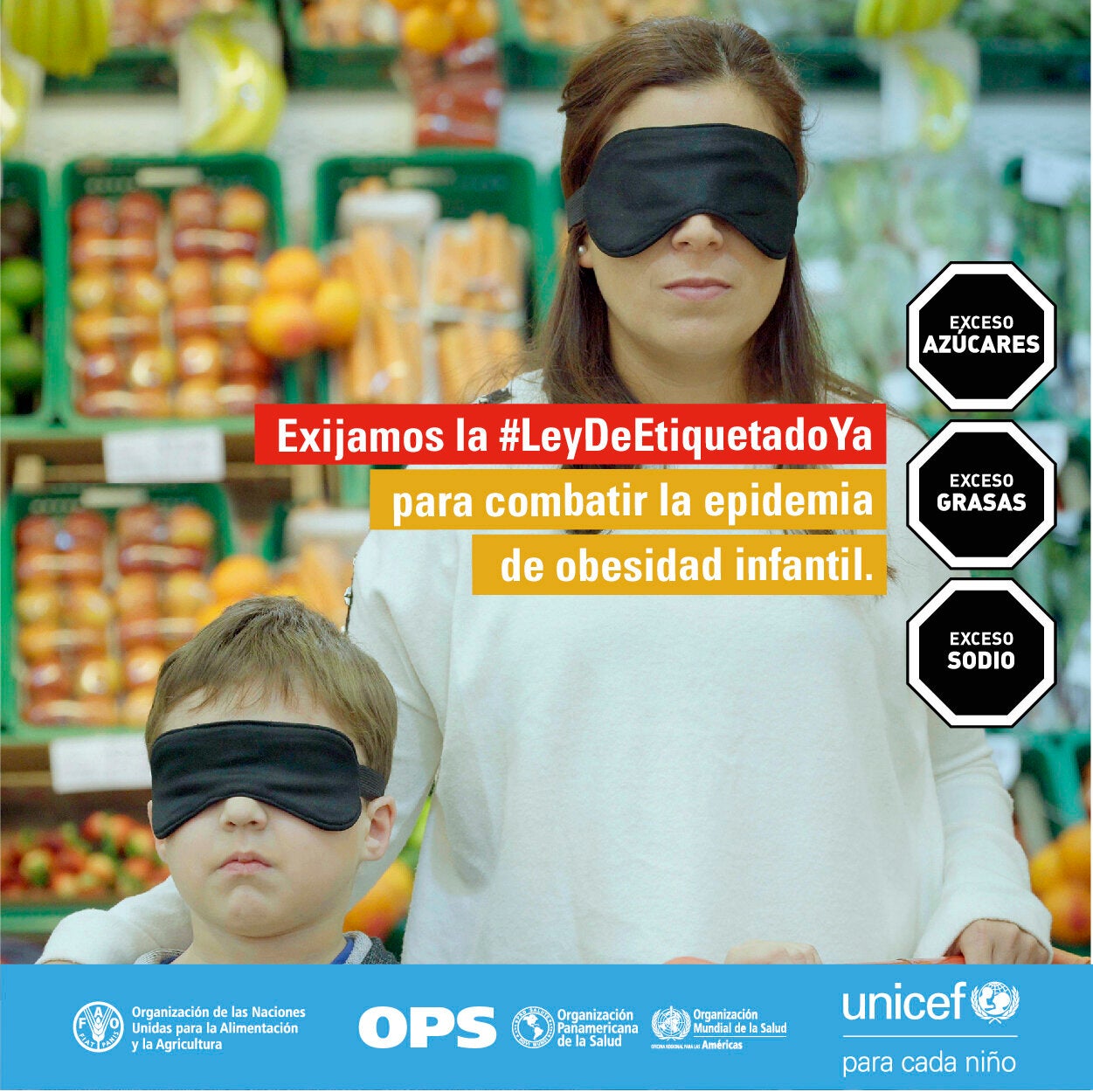

The excessive consumption of sugars, fats and sodium is a public health problem that is associated with the non-communicable diseases that most affect the population: overweight or obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and vascular, heart and brain diseases and kidney.

High blood pressure, high fasting blood sugar levels (measured as fasting plasma glucose), and overweight/obesity are the top three risk factors for mortality in the Americas. Unhealthy eating is closely linked to these top three risk factors in the Americas, driven largely by excess intake of sugars, total fats, saturated fats, trans fats, and sodium ― which are referred to as the “critical nutrients” of public health concern.

The excess intake of these nutrients has been driven largely by the widespread availability, affordability, and promotion of processed and ultra-processed food products that are excessive in sugars, fats, and sodium.

An essential part of the solution requires the use of laws and regulations to reduce the demand for and offer of products that contain excessive amounts of critical nutrients. One of the key policy tools to regulate such products to prevent them from unbalancing diets is the use of front-of-package labeling (FOPL) to indicate consumers which products contain excessive amounts of sugars, total fats, saturated fats, trans fats, and sodium.

The PAHO nutrient profile model allows the identification of products that should contain warnings on the front of the containers for their excessive content of critical nutrients that can affect health.

Front-of-package warning labeling is a simple, practical and effective tool to inform the public about products that can harm health and help guide purchasing decisions.