By Ingrid Cotto

Salsa's "golden boy" is paying tribute to his fans and the women in his life by joining with the Pan American Health Organization in a new campaign to end domestic violence.

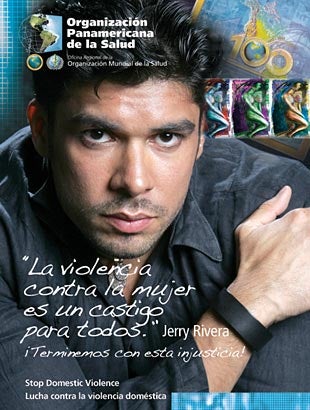

Washignton, D.C., 27 March 2008 (PAHO) - Jerry Rivera's website prominently features his PAHO public service announcement on violence against women.

Throughout Jerry Rivera's 18-year singing career, music has been his voice. Today, after recording 14 albums and selling 6 million copies, the former "Salsa Baby" is ready to send a grown-up message that goes beyond love songs.

Rivera is adding his voice to the growing chorus of celebrities and other advocates who want to see an end to domestic violence. In late 2006, he was named a Champion of Health by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and agreed to be the spokesman for a new campaign to stop violence against women and children, especially in Latin America and among Hispanics in the United States.

Don't bother calling me

I'm not the same person as before

You can't control me

Or hurt me anymore

They're the first lines of Rivers of Pain, recorded by Rivera and his sister Saned in 2005. The song and music video have become a musical manifesto for Spanish-speaking women struggling to overcome domestic abuse.

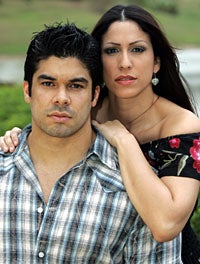

Jerry and sister Saned composed Rivers of Pain, a musical manifesto for Latina women struggling against domestic violence.

"This is just the beginning of a new stage in my personal life that I've now made part of my professional career," Rivera says. "This message goes wherever I go." Indeed, the anti-violence campaign that started at PAHO and is featured prominently on the singer's website has by now reached millions of Rivera's fans in the Americas and throughout the world.

Music in his veins

Far too many women need to hear Jerry Rivera's inspiring words. According to PAHO data, one in three women in Latin America and the Caribbean has suffered violence at the hands of a domestic partner, and much of the violence includes sexual abuse. The problem cuts across social, racial, religious, and geographical lines. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than three women are killed by their domestic partners every day in the United States.

"I've had female relatives very close to me who were abused since they were children," River says. "I'm going to do everything possible to make this message reach throughout the world." That's quite a goal for someone who never imagined his voice would be heard outside his native Puerto Rico.

Jerry was born Geraldo Rivera Rodríguez in the town of Humacao on July 31, 1973. In his case, it's no cliché to say he came into the world with music running through his veins. The Rivera family is rich in musical talent, from Jerry's tropical musician father, Edwin, to his older brother of the same name, to his younger sister Saned and two other brothers, Ito and José, who both play instruments professionally.

Almost as soon as he could walk, Jerry started accompanying his father and his mother, Dominga, to performances and eventually sang with them in their band, Los Barones Trio.

These early experiences shaped Jerry's own approach to family life. "It's one thing to be a father who shows up to enforce the rules and another to take your child to do things. My dad wasn't the kind who scolded me all the time, but the kind who shared things with me."

It was during one of his parents' shows that the famous Puerto Rican salsa band leader Tommy Olivencia heard Jerry sing. He offered to take him abroad and launch him on a solo career. But Jerry's father declined, proposing instead to record a demo for Jerry, which he personally financed.

Jerry vividly recalls arriving for that first recording session trembling with fear. "I would stop singing and cry for fear of making a mistake." To calm him down, the adults would take him outside for some fresh air and warm Caribbean sun.

In 1990, CBS Records saw potential in the baby-faced 15-year-old and signed him on as their youngest salsa artist. His first recording was aptly titled Beginning to Live. Rivera has fond memories of that first album, which he says set the stage for the series of autobiographical themes that has characterized his career.

"All my records are like that, if you listen to them. Beginning to live my big moment, beginning to struggle with my conscience, making decisions, trying new things, learning from my mistakes," he says. "You try out certain things, and you pick and choose what to keep in your life, the good things and the bad things you've done."

After Beginning to Live, Rivera's 1991 album Opening Doors did precisely that in Latin America and in Puerto Rico, where it climbed to the top of the charts and established the unique salsa style that has become Rivera's trademark. Breaking with the current trend, which focused heavily on street experiences, Rivera's music relied on romantic eroticism, and the feelings of a man who discovers the beauty of a woman for the first time.

There were those who thought salsa's new "golden boy" would be a passing fad. But the man who first launched Jerry on his career made a different prediction.

"Papi told everyone that I was the greatest. 'This is my son. He's bravo, just watch how far he goes.' I would tell him, 'Don't say that, there are so many people ahead of me.' But he'd say, 'You'll be next. You're the new generation.'"

It didn't take Jerry long to fulfill his father's dreams. In 1992, his album Count on Me sold more than a million copies, winning him two Lo Nuestro awards and 10 platinum records, and making music history as one of the best-selling salsa recordings ever. The young virtuoso who once threw "little paper love planes" in school was winning over legions of fans with his new salsa arias.

But despite his professional success—or perhaps in part because of it—there came a moment when Rivera wanted to do something more than sing love songs. It was a period when he felt surrounded by violence in his own country. "Every day I would wake up depressed ... seeing death all around me," he recalls.

When PAHO called to ask if he would become a spokesman against violence, Rivera was more than ready. Since appearing at the November 2005 celebration of International Day for the Elimination of Violence , he has recorded a public service announcement for PAHO's anti-violence campaign, has visited battered women's shelters in cities throughout the Americas, has participated in seminars and given radio interviews exhorting his fans to help bring an end to violence against women. He is also helping the Pan American Health and Education Foundation raise funds for programs to reduce violence and help battered women.

Today, Rivera says he feels deeply committed to the cause, to such an extent that he follows a number of cases personally, staying in touch with women who have decided to escape violent homes and try to build a better future.

Breaking the mold

Perhaps Rivera feels he has something to say about overcoming obstacles by drawing on one's inner strength. There was a period, in the late 1990s, when he wanted to experiment musically, to move beyond his own brand of salsa into new genres. But the recording industry was reluctant to let him to break out of the musical category that had brought him such success.

"The really famous singers, the big salsa stars, they told me I would fail—without me even asking their opinion, they had the nerve to tell me that," Rivera recalls with mild indignation. He decided to record Another Way, a 1998 breakaway record that included the bolero That One. The album spent several weeks as number one on Billboard's Latin charts and earned Rivera a Grammy nomination.

The singer enjoyed another moment of personal vindication when, in 2003, he performed his song Springtime with musical icon Carlos Santana. Rivera recalls something the famous guitarist told him at the time: "It doesn't matter if it's a bolero, or salsa; what matters is that it is you in whatever genre. Because all music come from Africa. It's not the style that makes the genre; it's you." The same year, Rivera recorded a sentimental tribute to a much-admired salsa predecessor. The album, I Sing to My Idol, Frankie Ruiz, won him a Latin Grammy nomination.

Today Rivera says he is grateful for his career success but also takes satisfaction from believing he's chosen the right path both professionally and personally. He credits the women in his life at least in part for this.

"I am privileged to have been born to a mother who took really good care of me. I have the best wife in the world, wonderful aunts, two daughters, so I am surrounded by women. I cannot get my head around the idea of abusing a woman."